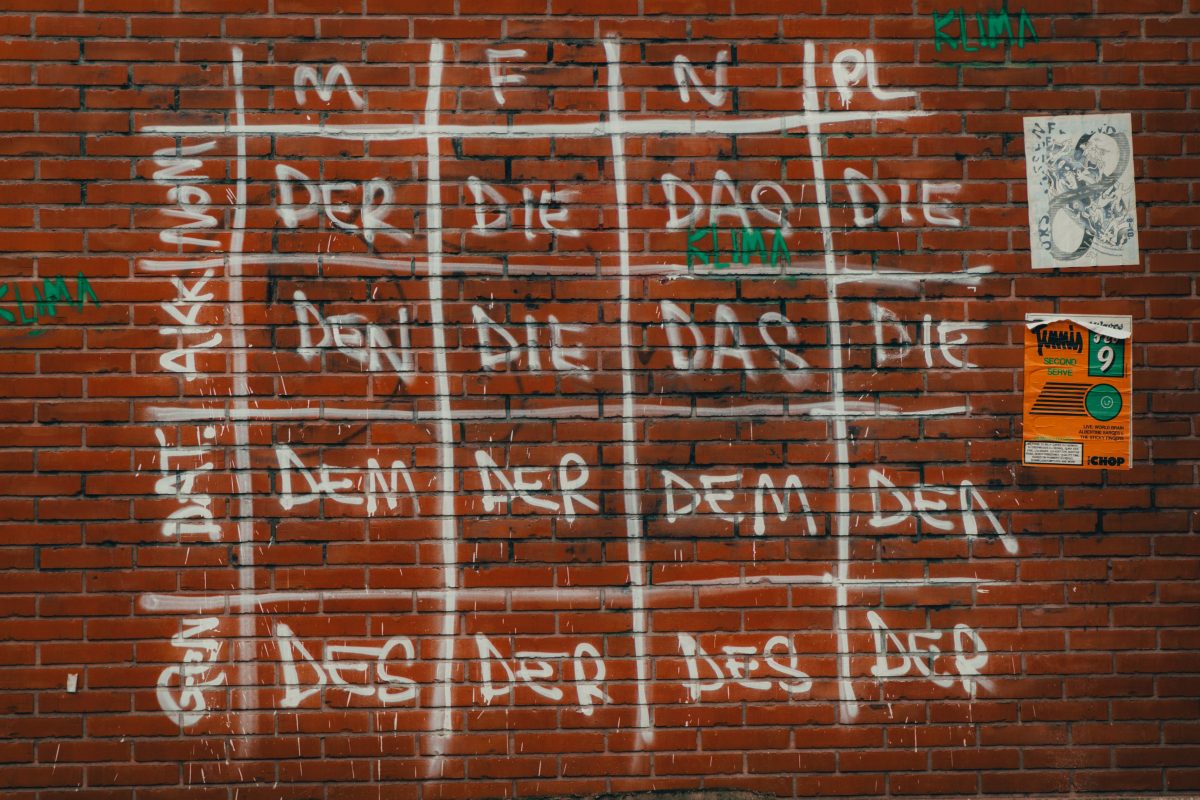

To many, German cases sound confusing and terrifying. They’re what people first tell you about when they try to scare you away from learning the language. But there is no reason to be put off by them! While many German speakers find cases scary, there are ways to tackle them and even eventually master them.

In this post, we will go over some of the basic German cases principles. By the end of it, you should be able to understand what cases are, what their use is, and how to recognize which case you need when.

What Are German Cases?

One of the reasons German cases might seem intimidating is that many people aren’t clear on what exactly cases are. If you are a new learner and an English speaker, the concept of cases might be foreign to you. So, let’s break it down.

A case (Kasus/Fall) is a grammatical category that tells you the function of a noun phrase in the clause. Now, that may sound complicated, but it’s actually pretty simple.

Basically, German cases tell you what role a noun (or a pronoun) plays in a sentence – they tell you if it’s a subject, direct object, or indirect object.

Note: Throughout this post, we will be using the word declension (or to decline). This means changing the form of a word, for example, to express the case of the word.

How Many German Cases Are There?

German has 4 cases in total. This may seem like a lot to you, but trust me: there are languages with far more cases than that. Czech has 7. Hungarian has 18. The German four really aren’t the end of the world.

What Are the German Cases?

The four German cases are as follows:

- Nominative (Nominativ) – the subject

- Genitive (Genitiv) – possession

- Dative (Dativ) – the indirect object

- Accusative (Akkusativ) – the direct object

Depending on which textbook you use, you may find these four in a slightly different order. Often, English teachers prefer to order the cases as follows: Nominative, Accusative, Dative, Genitive.

That said, the order we’ve used above is the order that Germans use. You might even come across some Germans referring to the nominative as the first case (der erste Fall). The genitive is the second case (der zweite Fall), the dative is third (der dritte Fall), and the accusative is fourth (der vierte Fall).

So, if you want to do what the native speakers do, we recommend using the order above.

Why Do You Need Cases in German?

German cases tell you what role a noun or a pronoun has in a phrase or a sentence. But why do we need this?

If you compare English and German, you may find that English has a pretty fixed word order. The typical English sentence structure is as follows: subject – verb – object

For example: The book belongs to the man.

- subject: the book

- verb: belongs (to)

- object: the man

You can’t mess around with the word order here without sounding like a certain green Star Wars character. Saying “To the man this book belongs” doesn’t sound right in English. But it could sound right in German.

The most basic rule for a simple German clause is this: the verb always comes second.

What about the subject? Unlike in English, the subject has a bit more flexibility in German. It doesn’t have to come first. Let’s take a look at the above sentence in German:

The German translation of The book belongs to the man is: Das Buch gehört dem Mann.

- subject: das Buch

- verb: gehört

- object: dem Mann

But you could also “Dem Mann gehört das Buch”.

If someone asks you who this book belongs to, and you want to emphasize that it’s that man’s, starting the sentences with dem Mann is a great way to do that. And it’s absolutely allowed! What sounds plain wrong in English is grammatically correct in German. The emphasis has shifted, but the meaning is still pretty much the same.

Now, if you know some very basic German, you may know that the man translates as der Mann. Yet, in this sentence, we say dem Mann. That’s because the word “man” here is declined (i.e., in a different case).

This is why a German person won’t ever look at a sentence such as “Dem Mann gehört das Buch” and think that the man belongs to the book. We know the man is the object here (i.e., who this belongs to) because of dem.

Let’s look at one more example: Ich habe den Apfel gegessen. (I ate the apple.)

- subject: ich

- verb: habe […] gegessen

- object: den Apfel

In a dictionary, you might find apple as der Apfel. In this case, we use den to illustrate that the apple is the object in that sentence – it’s being eaten. It’s not eating me. It’s not eating me even if I say: Den Apfel habe ich gegessen.

See how cases tell you so much about the noun in each sentence? By changing the case, you immediately get the idea of what the role of the apple is.

In the confusing world of the German language, German cases are there to help you figure out what someone’s trying to tell you. Once you understand what’s going on, the cases will actually make your experience with the language easier.

German Cases and Gender

One of the first things you learn about German is that nouns have gender. These are signified by the preceding article of each noun.

There are three genders in German:

- masculine: der Mann (man)

- feminine: die Frau (woman)

- neuter: das Kind (child)

When you’re trying to decline a noun in German, the article is what you need to change. The above articles (der, die, das) are all in the Nominative case.

This is when German cases get tricky. When you’re figuring out how to say a phrase or a sentence in German, chances are there will be some declension happening. To get it right, you need to use both the right case and the right gender of the word.

Without the correct gender, you might get the right case, but still say a grammatically wrong sentence. That’s because, for example, the dative of das (i.e., dem) looks different than the dative of die (der).

So, when you’re drilling all that vocabulary, please remember to learn the gender of each word. This is vital to your German. Without it, even the most detailed understanding of German cases won’t help you speak correct German.

Now, let’s finally have a look at each of the four cases in more detail, starting with…

The Nominative Case

The nominative case (Nominativ) is the simplest of them all. It’s the word in its most basic form. The version you’ll find in dictionaries. Der Mann. Das Auto. Die Sonne.

In a sentence, the nominative marks the subject of the verb. Let me explain what that means:

In German, the nominative is also sometimes called der Wer-Fall. Wer means who in German. Nominative is the who-case because it answers the question of who (or what (was) when talking about inanimate objects).

- Who is reading? – Maria (the subject) is reading.

- What is bright? – The sun (the subject) is bright.

Here are some examples in German:

- Das Fenster ist schmutzig. (Was ist schmutzig?)

- The window is dirty. (What is dirty?)

- Der Vater hat ein Auto. (Wer hat ein Auto?)

- The father has a car. (Who has a car?)

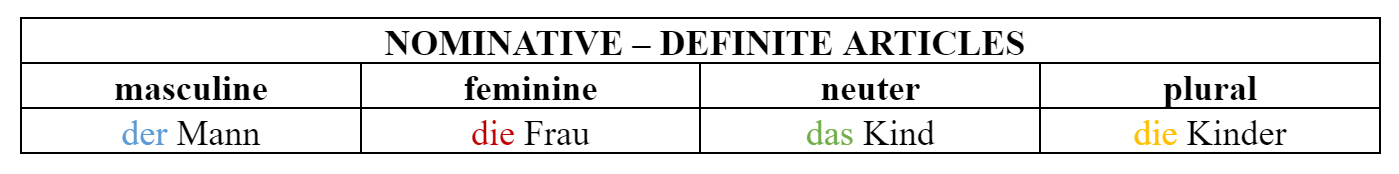

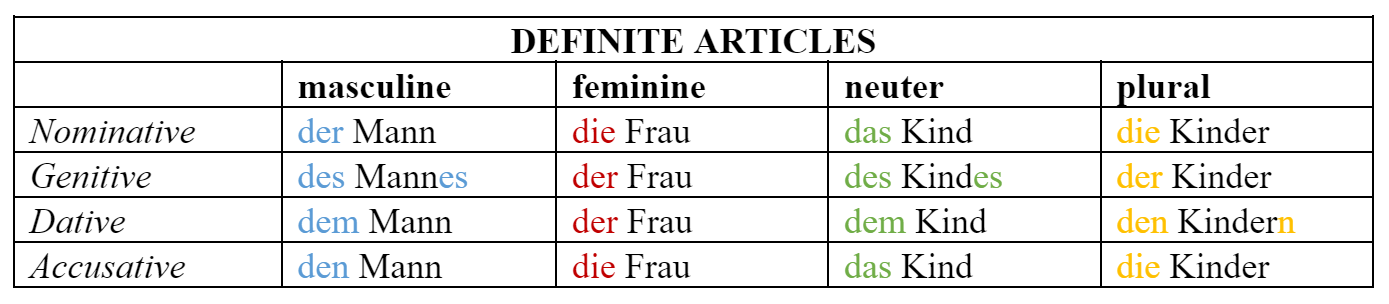

These are the nominative forms of nouns with a definite article:

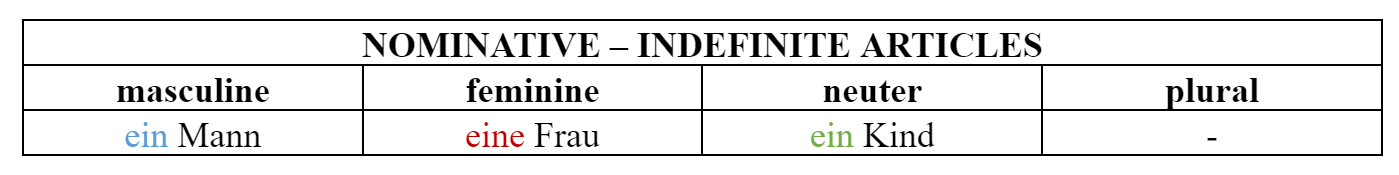

German also uses indefinite articles. Here are the indefinite articles in the nominative:

The Genitive Case

The genitive case (Genitiv) is the odd one out. It almost feels like the most obscure case.

It’s usually the case that your teachers will cover last. This makes sense – genitive is sort of doing its own thing. While the other cases are mostly used in relation to the verb in a sentence, the genitive is often more connected to other nouns.

The most common use of the genitive is to link nouns together, usually to signify possession. That’s why the genitive is also known as Wes-Fall or Wessen-Fall (whose-case).

Here are a couple of examples:

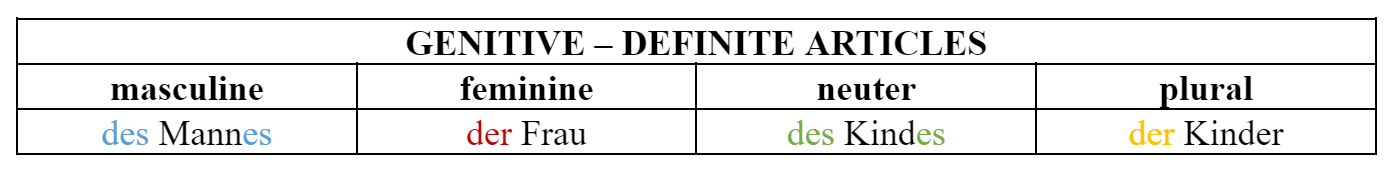

- der Hund des Kindes (the dog of the child – i.e., the dog that belongs to the child)

- The noun in the genitive here is das Kind. In genitive, das turns into des. Some nouns (such as Kind) also take an additional –(e)s ending in masculine and neuter.

- das Rad der Frau (the bike of the woman – i.e., the bike that belongs to the woman)

- der Ton der Gitarre (the sound of the guitar)

Let’s take a closer look at the different genitive article endings:

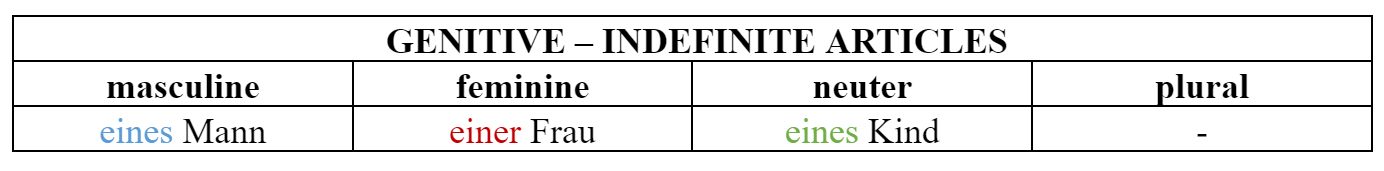

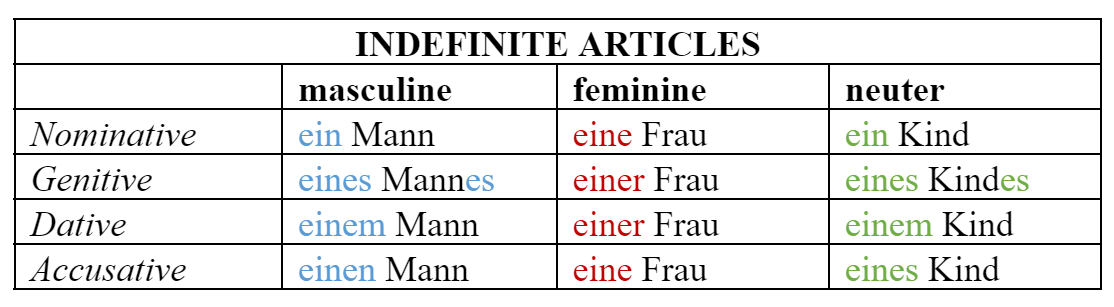

And for indefinite articles:

The Dative Case

The most common use of the dative case (Dativ) is as a marker of the indirect object of the verb. The indirect object could be described as the recipient of the direct object. Let’s look at the following sentence in English:

I am baking you a cake.

- I is the subject – the who of the action (Who is baking the cake? I am.)

- cake is the direct object – the what is being affected of the action (What is being baked? A cake.)

- you is the indirect object – the recipient of the direct object (Who am I baking a cake for? You.)

In German, we often use dative to indicate that something is an indirect object.

- Ich gebe dem Hund den Ball. (I give the ball to the dog.)

Like the previous two cases, the dative also has an alternative name: Wem-Fall, meaning whom-case. Wem (whom) is the question word you’d use to find out if a noun is in the dative.

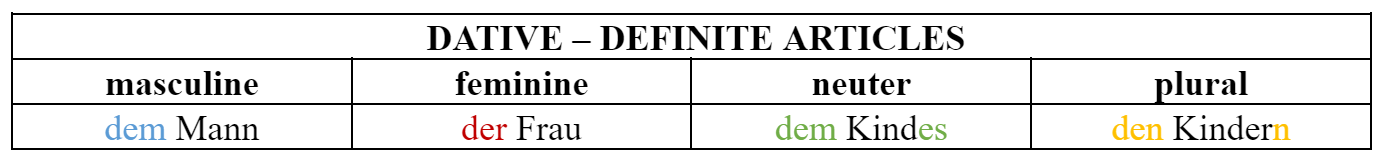

Now let’s look at the tables. Notice how in the dative plural, the nouns also take an additional -n ending:

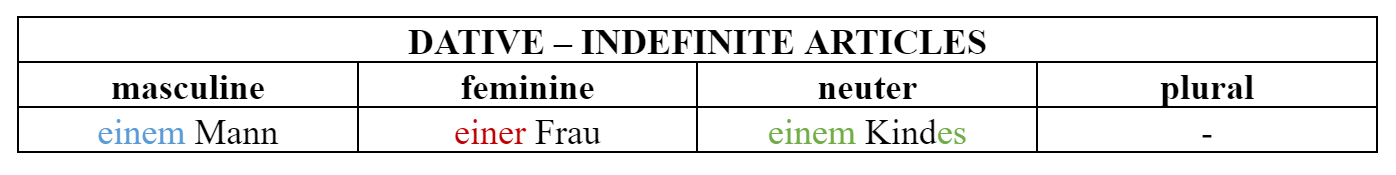

And for indefinite articles:

For a full overview, check out our comprehensive guide to the German dative case.

The Accusative Case

Last but not least, we have the accusative case (Akkusativ). This one is commonly used to mark the direct object of the verb. We’ve sort of covered this when we talked about dative, but just to illustrate:

I am reading a book.

- I is the subject (Who is reading?)

- a book is the direct object (What is being read?)

The accusative is also known as the Wen-Fall, which could be translated as the who-case. This is less helpful in English because who is also the translation for wer (and, technically, wem). So, just remember that the direct object is the person/thing that’s being directly affected by the action (verb).

In this German example, the pen is being bought – therefore, the pen is the direct object:

- Ich kaufe den Kugelschreiber. (I am buying the pen.)

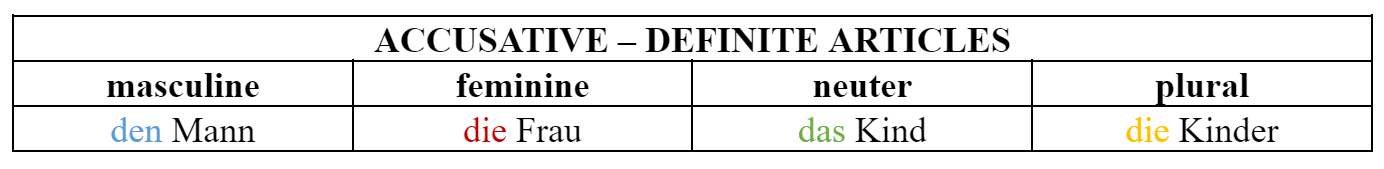

Definite articles in the accusative:

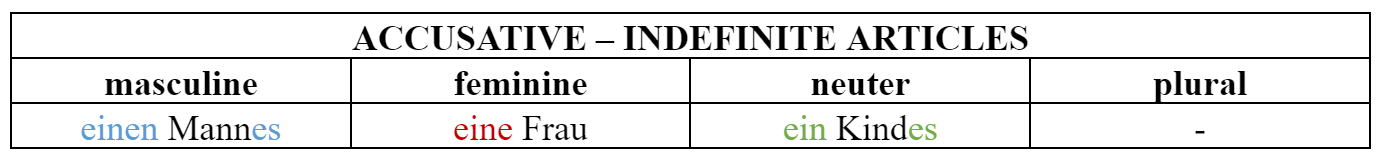

Indefinite articles in the accusative:

All the Cases Combined

Having eight separate tables might be great when you’re trying to understand each case for the first time, but it is not the most practical way of jotting everything down. That’s why we’ve also combined all that we’ve just covered into two all-encompassing tables.

This is the table for definite articles:

And for indefinite articles:

German Cases and Prepositions

Unfortunately, German cases don’t always just depend on their question word or function in the sentence. There are other markers of cases.

For example, some prepositions always follow a specific case. Let’s take a look at some of these:

Genitive prepositions

While the genitive is most commonly used to link two nouns, it can sometimes be used in other ways, too. For example, when you use a preposition that always takes the genitive.

Luckily, there are a couple of German prepositions that require the genitive case. These are:

- (an)statt – instead of

- trotz – despite, in spite of

- während – during (refering to time)

- wegen – because of

Whenever you see one of these four prepositions, remember that you always have to put the following noun in the genitive.

Dative prepositions

Dative takes more prepositions than the genitive. Again, the only thing you can do here is memorizing these.

Here are the most common dative prepositions:

- aus – out of, from

- bei – by, at

- gegenüber – opposite, towards

- mit – with

- nach – to, after, according to

- seit – for, since

- von – from, of

- zu – to, at, for

Accusative prepositions

Last but not least, here is a list of the most common accusative prepositions:

- bis – as far as, by, until

- durch – through, across

- für – for

- gegen – against

- ohne – without

- um – around, about, at

Prepositions with both dative and accusative

Some prepositions can be paired with both dative and accusative, depending on the context. These are: an (on), auf (on), hinter (behind), in (in), neben (beside), über (over, above, about), unter (under), vor (in front of, before), zwischen (between, amongst).

With these prepositions, the case you use will change the meaning.

- If you’re talking about position, use the dative.

- If you’re talking about direction, use the accusative.

This principle is explained exceptionally well in the following video by John Krueger:

German Cases: Some Other Considerations

There are some other rules when it comes to the usage of German cases. For example, like with prepositions, there are some verbs that always go with a specific case. We’ll go into more detail on that next time.

German cases may seem like an overwhelming topic, but it’s also one that gets simpler with time and practice. You can’t master it all in one day, but with enough work and patience, you’ll get there. Just keep working on those language skills and revising grammar.

Learn More about German Grammar

If you’ve got this far and still feel like checking out some more grammar articles, why not have a look at some of these:

- All You Need to Know about German Prepositions

- How to Make German Possessive Pronouns Yours

- A Comprehensive Guide to German Question Words

Clozemaster has been designed to help you learn the language in context by filling in the gaps in authentic sentences. With features such as Grammar Challenges, Cloze-Listening, and Cloze-Reading, the app will let you emphasize all the competencies necessary to become fluent in German.

Take your German to the next level. Click here to start practicing with real German sentences!

Dear Veronika,

Thank you for this excellent post that will surely help students of the German language. I noticed under the heading The Dative Case that in definite and indefinite articles you indicate dem Kindes and einem Kindes respectively. Also under accusitive case-indefinite articles you indicate ein Kindes. Also it shows einen Mannes. I would suggest that the above should be read as dem Kind, einem Kind, ein Kind, and einen Mann.

All the cases combined appear to indicate the cases correctly with the exception of under indefinite articles where you show accusative-eines Kind, which probably should read ein Kind.

I have written this in the spirit of assisting you. If I have misconstrued something, I am sure that you will put me straight on this.

The best resource so far, the only one I read that puts some logic behind all the complication. Thanks!