The Polish interrogative pronouns kto and co correspond to the English question words who and what, so their main purpose is asking questions about personal (human) and impersonal agents.

Kto wygrał konkurs? (“Who won the contest?”)

Co jeszcze widziałeś? (“What else did you see?”)

On a basic level, Polish interrogative pronouns are very much like their English equivalents: there is the personal variant kto (“who”) used to ask about people, and the impersonal variant co (“what”) used to ask about everything else. Of course, both are always placed at the beginning of a clause, unless preceded by a preposition.

However, one fundamental difference is that Polish interrogative pronouns are not immune to the influence of the grammatical case system – both of them have several forms which reflect their function in the sentence.

You can find something similar in English as well: the pronoun whom, a remnant of the old case system, was originally the dative form of the English personal interrogative pronoun. Because of that, it often corresponds to the Polish dative form komu:

To whom do we owe the discovery of penicillin?

Komu zawdzięczamy odkrycie penicyliny?

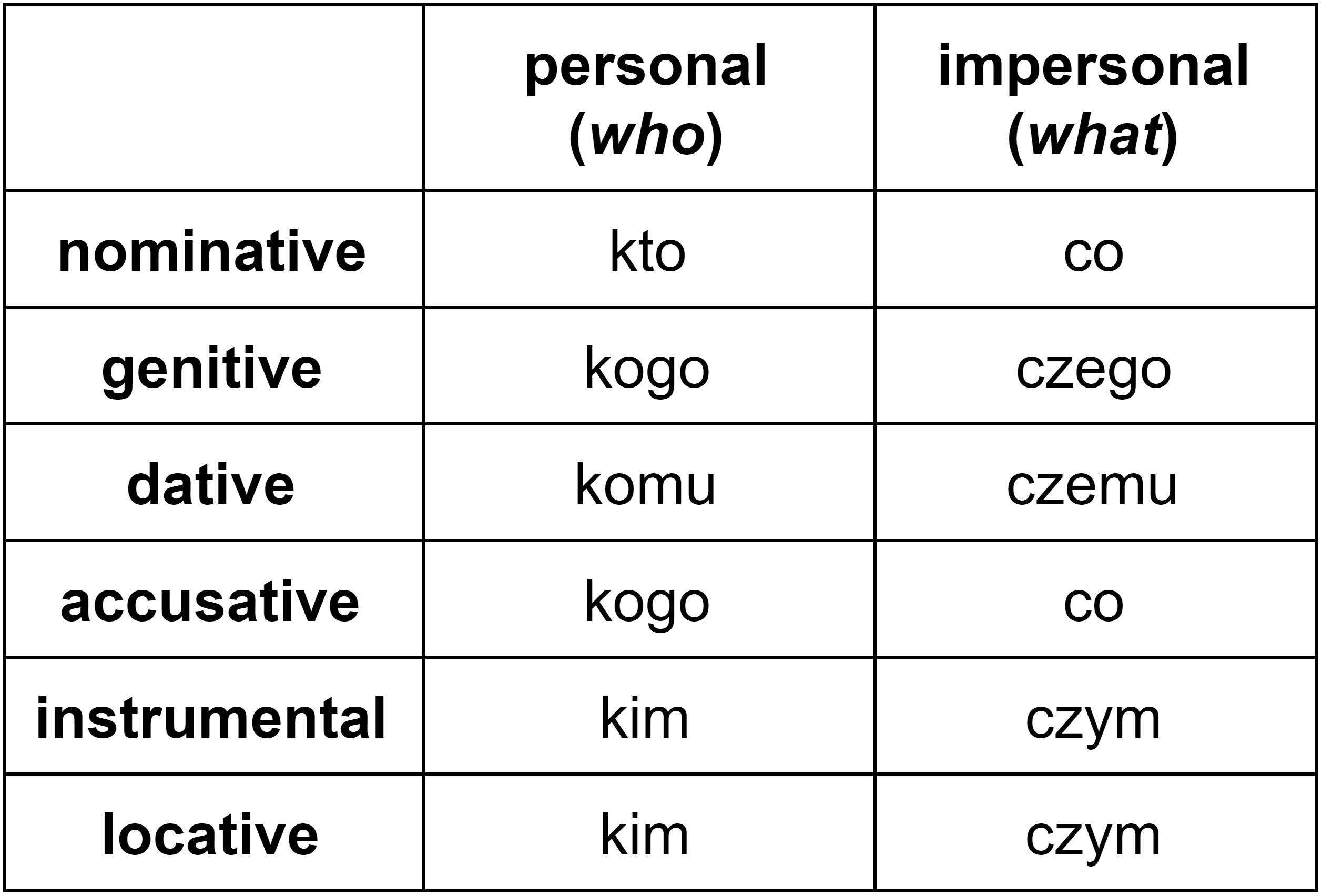

Grammatical case of the Polish interrogative pronouns kto and co

When using interrogative pronouns, you don’t really have to worry about choosing the correct gender or number. Whether you’re asking about a woman, a man or a group of people, you always use the same pronoun – the only meaningful distinction is that between the personal kto and the impersonal co. This means both words have six possible grammatical forms:

(If you’re often unsure whether to use who or whom in English, you should be thankful you don’t have to choose from six different forms…)

Luckily, once you understand how Polish cases work, it’s not so hard to recognize which form of kto or co is required in the given context.

Nominative: kto, co

The nominative forms kto and co are used to ask about the subject of the sentence. In other words, you mostly use them to ask:

- who or what does something,

- who or what is someone or something.

Kto zamknął drzwi? (“Who closed the door?”)

Kto jest twoim ulubionym nauczycielem? (“Who‘s your favorite teacher?”)

Co jadłeś na śniadanie? (“What did you have for breakfast?”)

Co jest w tej torbie? (“What’s in this bag?”)

Genitive: kogo, czego

The genitive forms kogo and czego are usually used to refer to:

- the direct object in a negative sentence,

- the direct object of verbs such as szukać (“to look for”), potrzebować (“to need”), or używać (“to use”),

- objects following prepositions dla (“for”), od (“from”), and do (“to”).

Kogo nie lubi Tom? (“Who doesn’t Tom like?”)

Kogo szukają ci policjanci? (“Who are these police officers looking for?”)

Czego nie mogę jeść? (“What can’t I eat?”)

Do* czego to służy? (“What is this used for?”)

Dative: komu, czemu

The purpose of the dative forms komu and czemu is referring to:

- the indirect object of the sentence (someone or something to whom or for whom an action is done),

- the object of verbs such as dawać (“to give”), wierzyć (“to believe”), dziękować (“to thank”), or pomagać (“to help”).

Komu dasz książkę? (“Whom will you give the book to?”)

Komu możemy zaufać? (“Whom can we trust?”)

Czemu zawdzięczam ten zaszczyt? (“To what do I owe this honor?”)

Czemu wierzysz, plotkom czy faktom? (“What do you believe, rumors or facts?”)

Accusative: kogo, co

The accusative forms kogo and co appear in questions asking about the object of the sentence – that is, the entity to which something is being done.

Kogo tam spotkałeś? (“Who did you meet there?”)

Kogo lubisz bardziej, mnie czy jego? (“Who do you like more, me or him?”)

Co ty tu robisz? (“What are you doing here?”)

Co otwiera ten klucz? (“What does this key open?”)

Instrumental: kim, czym

Uses of the instrumental forms kim and czym usually involve one of the following:

- the verbs być (“to be”), zostać (“to become”),

- certain prepositions, such as z (“with”), przed (“before” / “in front of”), and za (“behind”),

- questions about the means (= the instrument) used to do something.

Kim są ci ludzie? (“Who are these people?”)

Z kim poszłaś na plażę? (“Who did you go to the beach with?”)

Czym jest miłość? (“What is love?”)

Czym kroicie chleb? (“What do you cut bread with?”)

Locative: kim, czym

Finally, the locative forms kim and czym are only used together with certain prepositions, among others o (“about”), w (“in”), and na (“on”).

O kim mówisz? (“Who are you talking about?”)

O kim jest ten film? (“Who is this movie about?”)

W czym jesteś dobry? (“What are you good at?”)

Na czym smażysz rybę? (“What do you fry fish in?”)

Kto and co as relative pronouns

In English, a sentence doesn’t have to be a question to contain who or what. The two words can also be used as relative pronouns, whose purpose is to introduce additional clauses into the sentence. The same is true for Polish:

Wiesz, kim ja jestem? (“Do you know who I am?”)

Powiedz mi, czego potrzebujesz. (“Tell me what you need.”)

One thing that’s different to what you’re used to in English is the punctuation: relative clauses introduced by kto and co require a comma before the pronoun.

If you know how to use kto and co in questions, you’re all set. The rules for choosing the right grammatical case are exactly the same here.

Just like in interrogative sentences, the pronouns kto and co can be preceded by prepositions. These can never be moved to the end of the sentence:

Wiemy, dla kogo pracujesz. (“We know who you’re working for.”)

Nie rozumiem, do czego zmierzacie. (“I don’t understand what you’re driving at.”)

However, in some contexts, the appropriate pronoun might be który, rather than kto or co.

For impersonal objects, the rule of thumb is to use co where you would use what in English and który where you would use which.

Powiedz mi, czego się nauczyłaś. (“Tell me what you’ve learned.”)

Wymień słowa, których się nauczyłaś. (“List the words which you’ve learned.”)

There’s a similar rule of thumb when it comes to kto vs. który, though it’s a bit less intuitive and reliable: kto is mostly used after nouns, and który is usually used after verbs.

Chyba wiem, kto mógłby ci z tym pomóc. (“I think I know who could help you with this.”)

Znam człowieka, który mógłby ci z tym pomóc. (“I know a man who could help you with this.”)

(If you’d like to learn more about when and how to use który, see this article on Polish relative pronouns.)

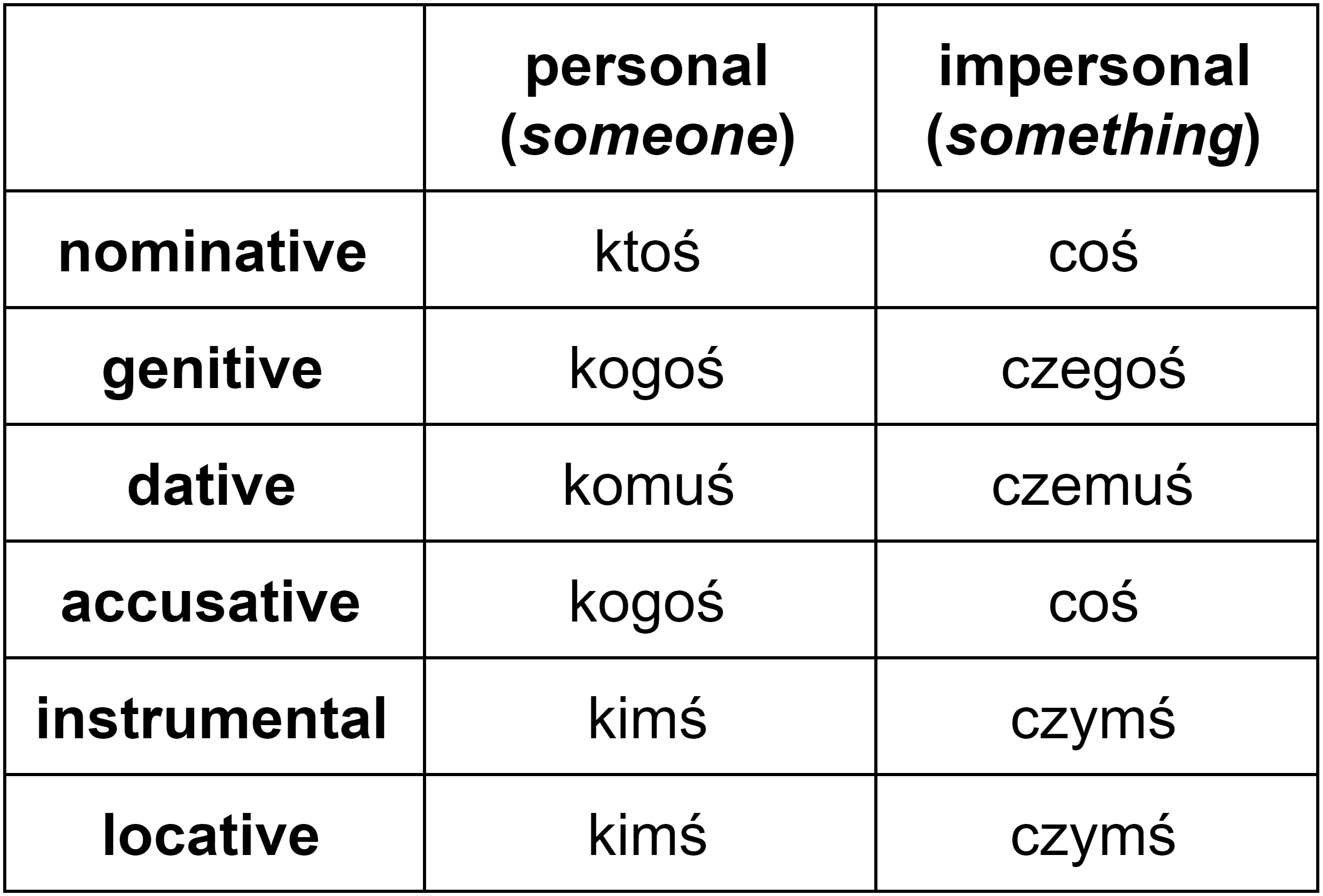

Polish indefinite pronouns ktoś and coś

When referring to something unknown or unspecified in English, you usually use indefinite pronouns, such as somebody (or someone) and something. In Polish, the equivalent indefinite pronouns are ktoś and coś.

Ktoś mnie obserwuje. (“Somebody’s watching me.”)

Mam coś dla ciebie. (“I’ve got something for you.”)

These are, of course, derived from kto and co. So if you’ve studied the interrogative pronouns before, you’ll find using ktoś and coś much easier. Just look at this declension table:

Though their role in a sentence is different, literally all the forms of ktoś and coś are created by adding -ś to the corresponding form of kto or co. The context for the use of particular grammatical forms is also the same as in interrogative pronouns. Below are a few examples:

Pożyczę od kogoś parasol. (“I’ll borrow an umbrella from somebody.”)

Chcemy ci coś powiedzieć. (“We want to tell you something.”)

Tom sprzedał to komuś innemu. (“Tom sold it to somebody else.”)

Chciałabym porozmawiać z tobą o czymś innym. (“I’d like to talk to you about something else.”)

Moreover, ktoś and coś can also correspond to anybody (or anyone) and anything when used in questions and some negative sentences:

Czy ktoś tu zna francuski? (“Does anybody here know French?”)

Czy możemy ci w czymś pomóc? (“Can we help you with anything?”)

Czy Tom się z kimś spotykał? (“Was Tom dating anybody?”)

Nigdy czegoś takiego nie widziałem. (“I’ve never seen anything like this.”)

It is important to note that not all instances of anybody and anything in English can be translated as ktoś/coś. Most negative sentences will have the negative indefinite pronouns nikt (“nobody”) and nic (“nothing”) instead:

Nie znam nikogo w Bostonie. (“I don’t know anybody in Boston.”)

Tom jeszcze o niczym nie wie. (“Tom doesn’t know anything yet.”)

(To find out more about the pronouns nikt and nic, read the article on negative pronouns.)

Finally, ktoś and coś can also appear together with kto and co, like in the examples below:

Ktoś, kto wygląda jak Tom, stoi obok bramy. (“Someone who looks a lot like Tom is standing near the gate.”)

Potrzebuję czegoś, co mógłbym jej dać. (“I need something that I could give her.”)

The Polish Pronoun Grammar Challenge

You can only learn so much from grammar explainers. The real expertise comes from actually using the language you’re studying.

Click here to start practicing kto(ś), co(ś), and other Polish pronouns by filling in the gaps in Clozemaster’s Polish Pronoun Grammar Challenge.

Come back to this article if you ever feel confused – it’ll help you get back on track and reinforce what you’ve learned.