German word order seems pretty straightforward to an English speaker – at first. However, pretty soon you will be finding that using English logic to build sentences leads to perplexed looks from the people you’re speaking to. Fortunately, like everything in German, there are rules which can help you out with the German sentence structure.

Understanding German Sentence Structure

Basic Word Order in German

As you, the intrepid German learner, may have already noticed, German has a very similar sentence structure to English, on the surface of it. There is a tasty sandwich of Subject, Verb and Object in both of them. Let us compare the English and German versions of the same sentence:

The man hits a ninja.

Der Mann schlägt einen Ninja.

- If we ignore the noun gender and cases, this is the same sentence in both languages. It starts with the subject, and is followed by the verb, which is followed by the object. This would not be the case in Japanese, where both the subject and object would come before the verb, so count yourself lucky that you chose to learn German, and not Japanese.

What are Clauses, anyway?

Clauses are coherent meaning units inside a sentence. In English and German, a clause must have a subject and verb in order to be a clause. In the sentence,

“I am handsome, but I am not interesting,”

there are two clauses: “I am handsome,” and, “I am not interesting.” Both of these are main clauses.

You may be wondering what a main clause is. It is one of the two types of clauses: main and subordinate.

- A main clause (Hauptsatz) is one that can stand alone and make sense, for example, “I am handsome.”

- A subordinate clause (Nebensatz) is a clause that cannot stand alone because that would make it illogical. Think, “Because there is a bear in my house,” or, “If he is married.” These have to be attached to other cohesive meaning units (AKA clauses) to be grammatically correct. For example, “Because there is a bear in the house, I am afraid to get snacks,” or, “I don’t know if he is married or not.” As you will see, German Nebensätze have other issues beyond making no sense alone, but first let’s delve into the main clauses.

Main Clauses (Hauptsätze)

As previously mentioned, a main clause is just a subject-verb meaning unit with an optional object (and also optional details). However, there is one thing about German sentences which gets English speakers EVERY TIME and is the key to understanding German sentence structure. Behold the English and German versions of this sentence:

Yesterday, I visited the doctor.

Gestern habe ich den Arzt besucht.

Notice anything… surprising? The German word order is different from the English one. In English, I can add ‘yesterday’, an adverb, at the beginning of the sentence, and the rest of the sentence remains the same. Woe betide you if you do this with a German sentence, however. This is because you would be breaking the cardinal rule of the German main clause:

The Verb Second Rule AKA Verb Position 2

No matter if the subject or an adverb comes first (meaning they are at Position 1), the conjugated verb must always be at Position 2 in the sentence. This is why both of these sentences are equally correct:

- Gestern habe ich den Arzt besucht. (More emphasis on the ‘yesterday’ aspect)

- Ich habe gestern den Arzt besucht. (More emphasis on the ‘me’ aspect)

Please note that if the subject comes first in the sentence, the adverb (if there is one) will immediately follow the verb. Similarly, if the adverb (most commonly an adverb of time) comes first, the subject will come immediately after the verb.

Subject + Verb + Adverb + other stuff OR

Adverb + Verb + Subject + other stuff

Here are some bonus example sentences in both versions so you can get a feel for German word order:

- Das Schaf hat gestern meinen Pulli gegessen. (The sheep ate my sweater yesterday)

- Gestern hat das Schaf meinen Pulli gegessen. (Yesterday, the sheep ate my sweater)

- Ich komme jeden Tag spät an. (I arrive late every day)

- Jeden Tag komme ich spät an. (Every day, I arrive late)

- Ich habe komischerweise meinen Stift verloren. (I have, strangely, lost my pen)

- Komischerweise habe ich meinen Stift verloren. (Strangely, I have lost my pen)

Subordinate Clauses (Nebensätze)

To recap, subordinate clauses cannot stand on their own and probably really need therapy. Not only this, but the word order once again surprises us in German. Let us look at two example sentences:

- Weil es einen Bären in meinem Haus gibt, habe ich Angst, einen Snack zu holen. (Because there is a bear in the house, I am afraid to get snacks)

- Ich weiß nicht, ob er verheiratet ist. (I don’t know if he is married)

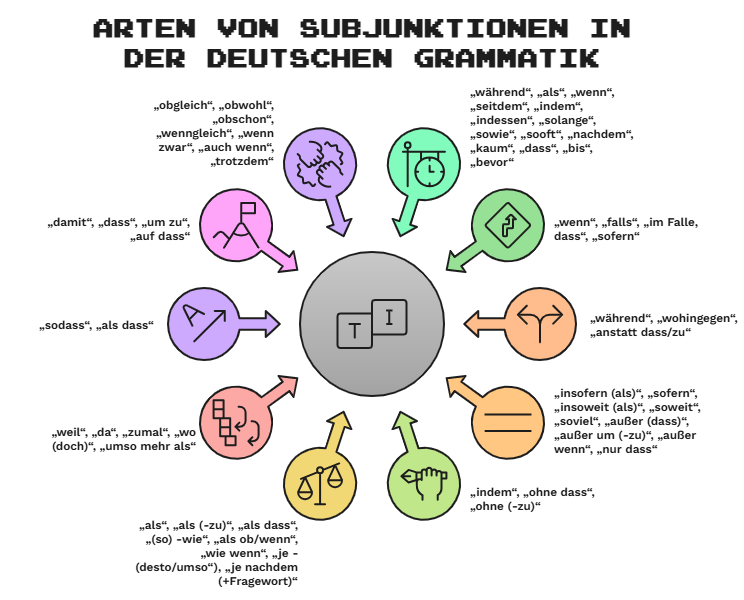

What do you notice about the verbs in these subordinate clauses? (Those are the green ones) Yup, the conjugated verb is right at the end. You may be asking yourself how you will know when it is a subordinate clause, and the answer is that you will slowly memorize all the conjunctions that do this (also known as subjunctions). Here they all are:

There is no need to rush to memorize these! They cover all subjunctions from A1 to C2 level, so you’ve got time.

Perhaps you are already planning how you can avoid subordinate clauses in German, but I challenge you to go a whole day without saying, ‘because’, ‘if’, ‘when’, ‘while’ or ‘until.’ It would be tough going!

If you can accept this word order and just remember that every one of these conjunctions sends the conjugated verb to the end, you will be a subordinate clause master in no time.

The Subordinate Clause with no Conjunctions

There is one more type of subordinate clause which has not been mentioned or even diagrammed yet, and that is the relative clause. In English, this would be a sentence like:

He is the man who has long eyelashes.

Er ist der Mann, der lange Wimpern hat.

Another version uses question words, such as ‘wie’, ‘wo’, ‘wann’, or ‘warum’.

I don’t know why he hid the cake.

Ich weiß nicht, warum er den Kuchen versteckt hat.

As you can see, both of these types of sentences also have the verbs at the end.

Check out these example sentences and see if you can spot if the word order is because of the conjunction or because it’s a relative clause:

- Er hat nie eine Freundin gehabt, obwohl er sehr nett ist. (He has never had a girlfriend, although he is very nice)

- Ich weiß genau, wer mein Nilpferd entführt hat. (I know exactly who kidnapped my hippopotamus)

- Es ist der Hund, den ich auf der Straße gesehen habe. (It’s the dog that I saw on the street)

- Ich lese dieses Buch, weil es interessant ist. (I am reading this book because it is interesting)

- Das ist das Buch, das ich im Internet gekauft habe. (This is the book that I bought on the internet)

- Ich habe ein Nilpferd, damit ich bequem reiten kann. (I have a hippopotamus so I can ride comfortably)

Pssst, the conjunctions/subjunctions are sentences 1, 4, 6 and the relative clauses are sentences 2, 3, 5.

Main vs. Subordinate Clauses: The Final Battle

Main and subordinate clauses don’t need to compete because they need each other to function, but if they were going to, these would be their stats:

| Main Clause | Subordinate Clause | |

| Can stand alone | √ | x |

| Conjugated Verb at Position 2 | √ | x |

| Conjugated Verb at the End | x | √ |

| Used after subjunctions | x | √ |

| Used in relative clauses | x | √ |

If you are still confused, studies show that consistent exposure to correct sentences improves your feel for a language. Listening and active recall also strengthen learning. Lastly, speaking the sentences out loud solidifies what you have learned and automates the correct grammar so you can use it fluently if you need it. If only there were a tool which could combine all of these…

Clozemaster has been designed to help you learn the language in context by filling in the gaps in authentic sentences. With features such as Grammar Challenges, Cloze-Listening, and Cloze-Reading, the app will let you emphasize all the competencies necessary to become fluent in German.

Take your German to the next level. Click here to start practicing with real German sentences!