Personal pronouns – words like I, she, or they in English – are used to refer to a specific entity in the world (usually a person) without actually naming it.

Just imagine how messy our everyday communication would be if we weren’t able to refer to someone as he, or to something as it. Using personal pronouns helps us save time and effort, and that’s why they are an essential part of a vast majority of languages, including Polish.

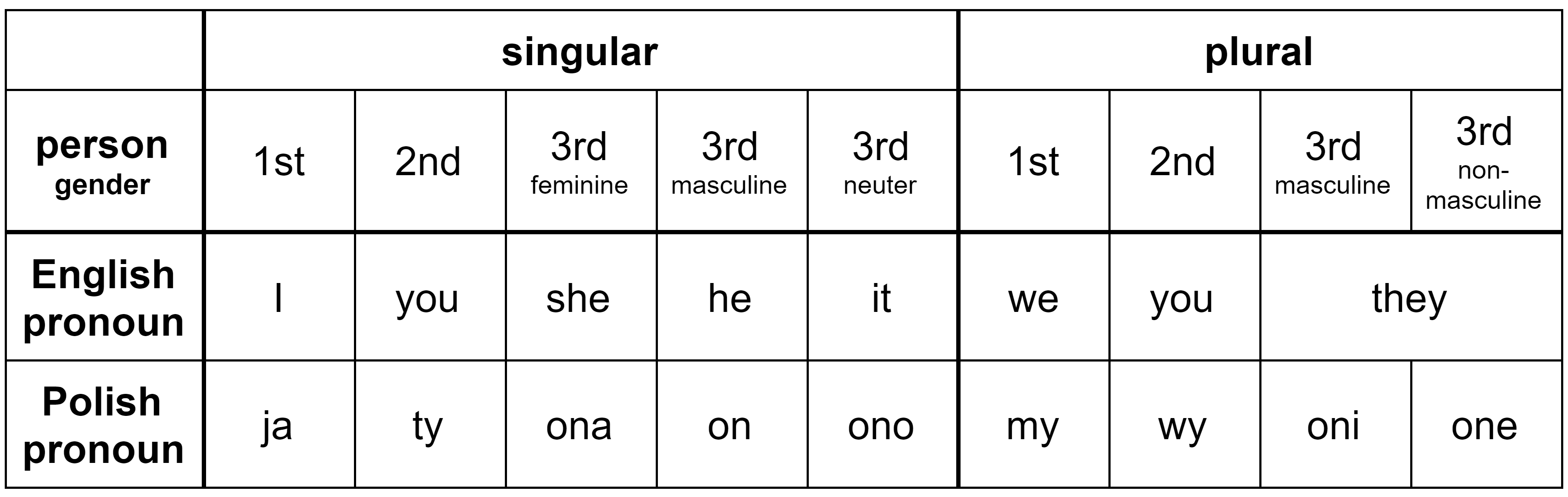

Number and gender of Polish personal pronouns

As you probably know, every Polish noun has a fixed grammatical gender. So when a pronoun is used in place of a noun, the pronoun’s gender must be the same as the noun’s gender.

This, however, only applies to third person pronouns, since first and second person pronouns do not distinguish between genders. Ty (singular you) will always be ty, regardless of the person’s gender.

Applying this rule to nouns for people should be pretty intuitive, as the same thing happens in English: you say he when talking about a man, and she when talking about a woman.

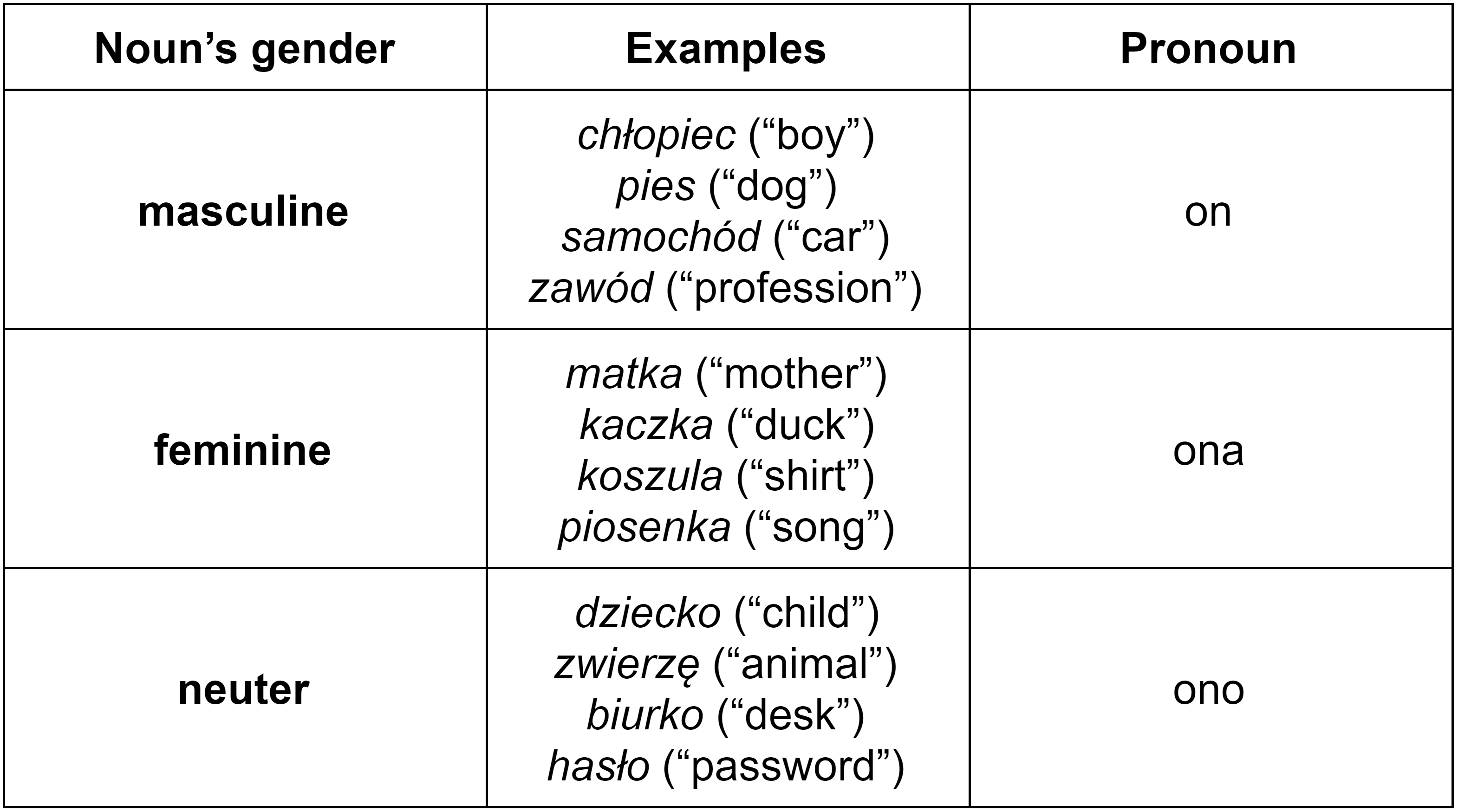

However, when referring to animals, objects or concepts, you can’t always expect ono to be the correct pronoun (even though its direct translation is it). This is because every Polish impersonal noun has fixed grammatical gender – masculine, feminine, or neuter – just as personal nouns do.

If a noun for an animal, object or concept is of feminine gender, you should refer to it using the third person feminine pronoun ona. If it’s of masculine gender, the corresponding pronoun is on. And if it’s neuter, you can go ahead and use ono.

Compare the examples below:

You might notice that all these examples are in the singular. What about plural personal pronouns?

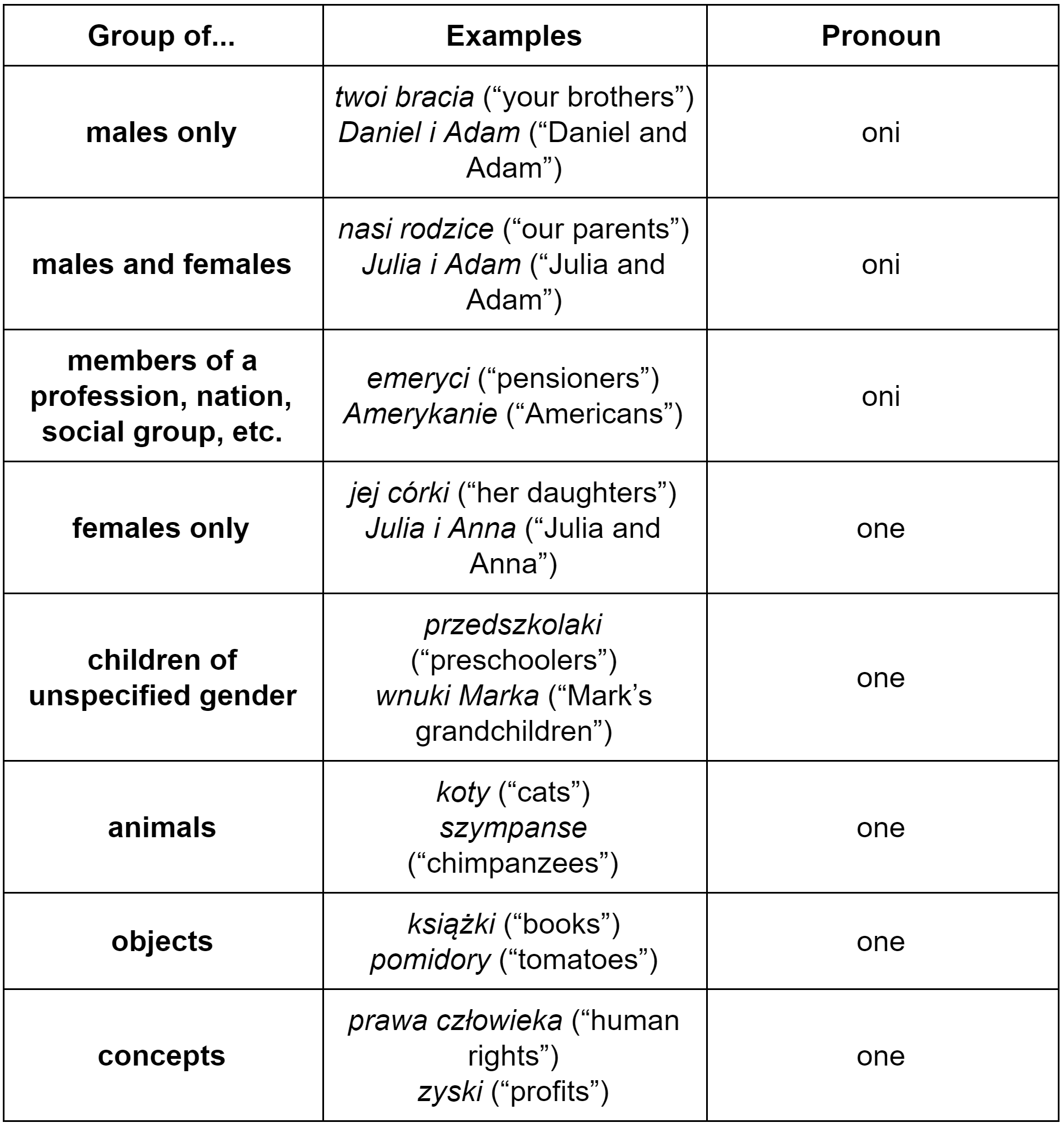

If you go back to the first table and look at the Polish equivalents of the pronoun they, you’ll notice a distinction that doesn’t exist in English: oni is the third person plural masculine pronoun, while one is the third person plural non-masculine pronoun.

This means that when choosing which plural pronoun to use, you have to take into account the gender of the entities it stands for.

If the pronoun is supposed to refer to a group with at least one male in it, the correct word to use is oni. This pronoun is also used when the gender of the people in the group is unknown – either because we don’t know who its members are, or because we’re generalizing about a social group that is likely to include both men and women.

In all other cases, the default third person plural pronoun is one. You’d use it to talk about groups of women, children, animals, objects, or concepts.

If you’re not entirely sure if you understand the distinction, this chart should help:

One more thing: unlike in English, Polish personal pronouns distinguish between singular you and plural you.

In other words, when you use ty, it’s always clear that you’re referring to a single person. Likewise, wy will always refer to more than one person (just like you all in English).

Grammatical case of Polish personal pronouns

Things are going to get a bit more complex now. Apart from number and gender, Polish pronouns have “inherited” one more feature from nouns: grammatical case.

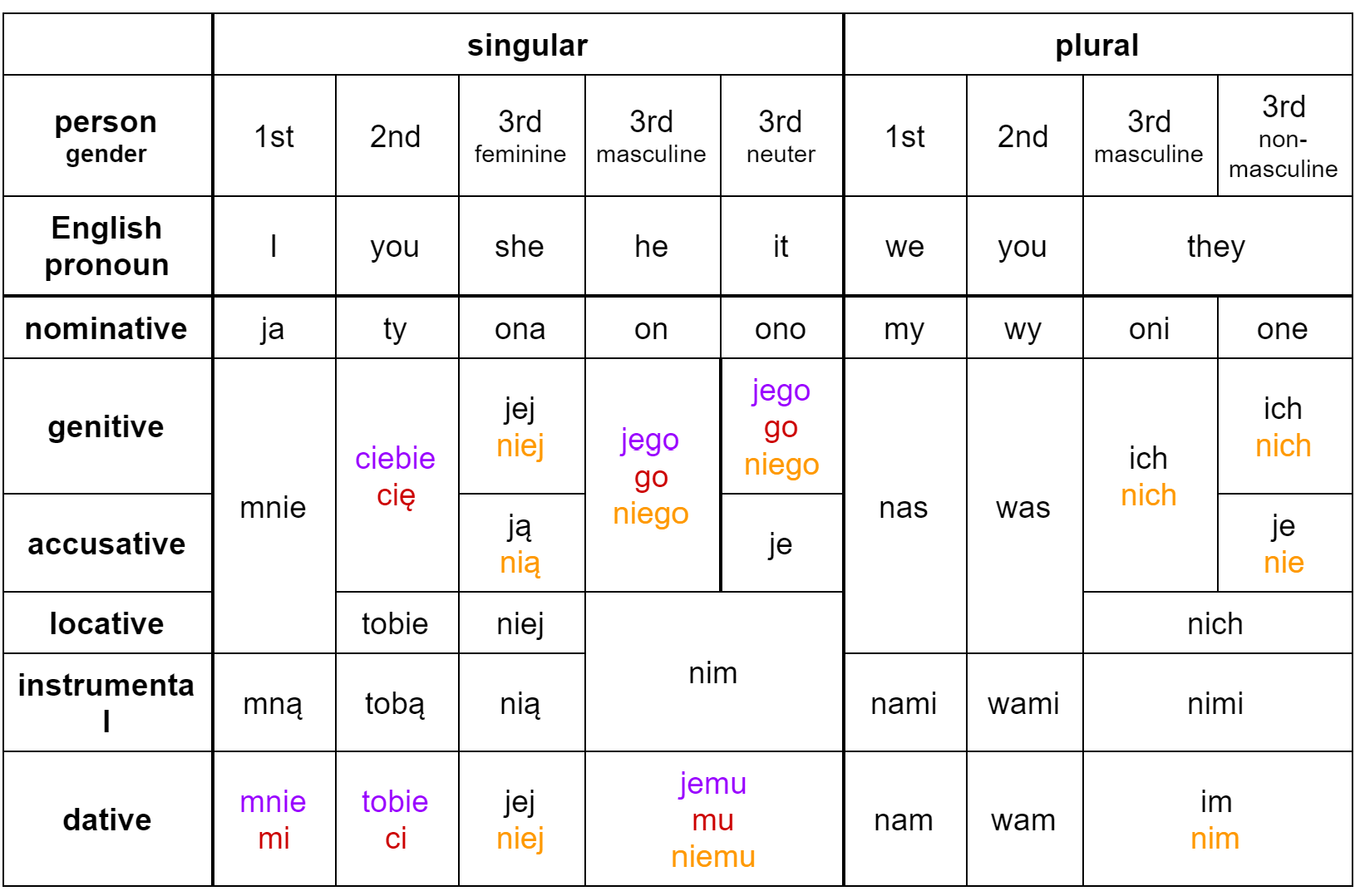

For the sake of simplicity, the previous section discussed only one of six potential cases: the nominative. This means that each of the nine basic pronouns listed there has five more forms. Well, at least in theory: some forms are shared between a couple of cases, so the final number of possible forms isn’t as overwhelming as you might expect.

Once again, making sense of this topic should be much easier if you consult this (rather extensive) pronoun chart:

So many forms… how do you know which one you should use?

Most often, you consider the pronoun’s role in the sentence, just as you would do when dealing with nouns and adjectives. Let’s take a look at the following sentence:

On ją kocha. (“He loves her.”)

Although it might not look like it, ją is the accusative form of the third person feminine pronoun ona (“she”). The pronoun takes the accusative case to reflect its role in the sentence: it is the direct object of the verb kochać (“to love”).

Naturally, if we were to replace the pronoun with a noun, the noun would still be in the accusative. It’s all about the context created by the verb.

Note that if you speak English, this kind of change (ona → ją) might actually feel quite natural. After all, English pronouns have distinctive forms used for objects as well: you say “He loves her”, and not “He loves she”.

Here is another sentence with a declined personal pronoun:

Chcesz ze mną zatańczyć? (“Would you like to dance with me?”)

The word mną is the instrumental form of the first person pronoun ja (“I”). In this case, the grammatical case of the pronoun is imposed by the preposition ze (“with”) which immediately precedes it.

Just like verbs, prepositions affect the grammatical case of pronouns that come after them (if you’d like to learn more, read this article on the relationship between Polish prepositions and grammatical case).

Let’s see what happens when a personal pronoun is used as an object in a negation:

On jej nie kocha. (“He doesn’t love her.”)

As you might have noticed, the sentence is very similar to one of the previous examples. Only this time, instead of the accusative, the pronoun ona takes the genitive case and changes its form into jej.

This is because the negation (expressed with the negative particle nie) forces the verb to “forget” its default case: while kochać (“to love”) normally requires its object to be in the accusative, nie kochać requires the genitive. This rule applies to direct objects in all negative sentences.

Prepositional pronouns in Polish

Now, consider this simple sentence with another form of the pronoun ona:

Mam dla niej prezent. (“I’ve got a gift for her.”)

Even though the niej form looks different to the jej form in the previous example, they are actually both genitive forms of the pronoun ona.

You see, some pronouns have two or three forms for a single grammatical case. While jej could be considered the default genitive form, niej is an alternative form only used after prepositions, such as dla in the above example.

And why is that? There’s just something about prepositions that makes them force third person pronouns (on, ona, oni, one) to assume forms starting with n-.

For your convenience, all these “n- forms” have been marked orange in the table at the beginning of the section.

Short and long pronoun forms in Polish

If you take a closer look at the table, you’ll notice that the n- forms aren’t the only alternative pronoun forms. There’s another distinction at play here: some singular pronouns have short and long forms which are used in different contexts.

Once again, all short and long forms have been color-coded in the table: long forms are marked purple, and short forms are marked red.

Below are three most important contexts in which you should always use the long form:

1. When a pronoun follows a preposition. However, this rule doesn’t apply if the pronoun also has an n- form – these always get priority when it comes to prepositions.

Czekam na ciebie. (“I am waiting for you.”)

NOT: Czekam na cię.

2. When a pronoun is used at the beginning of a clause.

Ciebie nie zapraszałam. (“I didn’t invite you.”)

NOT: Cię nie zapraszałam.

3. When a pronoun is stressed for emphasis or clarification.

Kocham ciebie, nie jego. (“I love you, not him.”)

NOT: Kocham cię, nie go.

Outside of the three contexts above, you’re often free to use either form, but the short form will be a much more natural choice in most situations. Below are a few example sentences where the short form makes more sense than the long one:

Lubię cię. (“I like you.”)

Nie znam go. (“I don’t know him.”)

Kto mu pomaga? (“Who is helping him?”)

The Polish Pronouns Grammar Challenge

If you’ve made it all the way through this article, you have a pretty good idea of why Polish pronouns seem to have an infinite number of forms. What’s even more important, you’ve probably noticed that behind it all are (mostly) reasonable rules that can be easily learned and internalized.

What’s next? As always, once you’ve got a basic theoretical understanding of the topic, the most effective way to master it is to follow up with as much practice as possible until you’re satisfied with the result.

The Polish Pronouns Grammar Challenge lets you practice using pronouns in real Polish sentences with immediate feedback to help you improve. Click here to take up the challenge!

Extremely helpful. Am studying Polish on Duolingo, which doesn’t give as many Grammar Tips for Polish as it does for other languages. Every language seems to have one (possibly two) elements that are a real nuisance for foreigner learners: apparently, it’s the verb “to go” in the Apachean languages, e.g. In Polish, it’s obviously the pronouns. Sigh….

the verb to go is also confusing in Polish lol I still never know which verb to use

Thank you so much, this an amazing helpful blog.

The difficulties that I found during the learning for Polish language(as a foreigner) is to remember the variation for verbs, nouns , adjective (odmiana, koniugacja) ,,,, so on and how they change by the cases of the sentences, in addition to how to write the phrases, vocabulary and sentences correctly,

I’m learning by myself using books, software, websites, dictionaries this make my progress slowly cause i was confuse how start in right way , i was reading tips , advices and every time i was see my self wasting a time without get the right progress

I see the learning for any language needs a lot of patience and practice.

Languages have keys to be learned, and during my learning I found some keys made me able to continue my way,

Polish Language is a beautiful as Polish people are so amazing and so nice.

Very nice job done here. Thank you for it and congrats! 🙂

If I had seen this table, I wouldn’t have married a polish woman ( anyone would write this sentence in Polish? )

Very thorough explanation. Polish grammar is Byzantine. I’ve read that it is the most inflected language in the world. This makes it extremely difficult to learn. I’m extremely frustrated with it. If the Poles think there is a logic to it certainly escapes me.